By Teresa Collis – Little Things Genealogy

Every genealogist knows that even the littlest details in a document can reveal a wealth of information. Death certificates, in particular, often stop us in our tracks. The names and dates are quite familiar, but the causes of death — those brief notes written in a doctor’s hand — can seem like a different language altogether.

Before the twentieth century, medicine had fewer tools to measure, test, or confirm disease. Diagnosis often depended on observation and experience rather than evidence. As a result, many early death certificates describe symptoms instead of causes — a reminder that the words we now read clinically were once part of a deeply human attempt to make sense of life’s end.

The shifting language of medicine

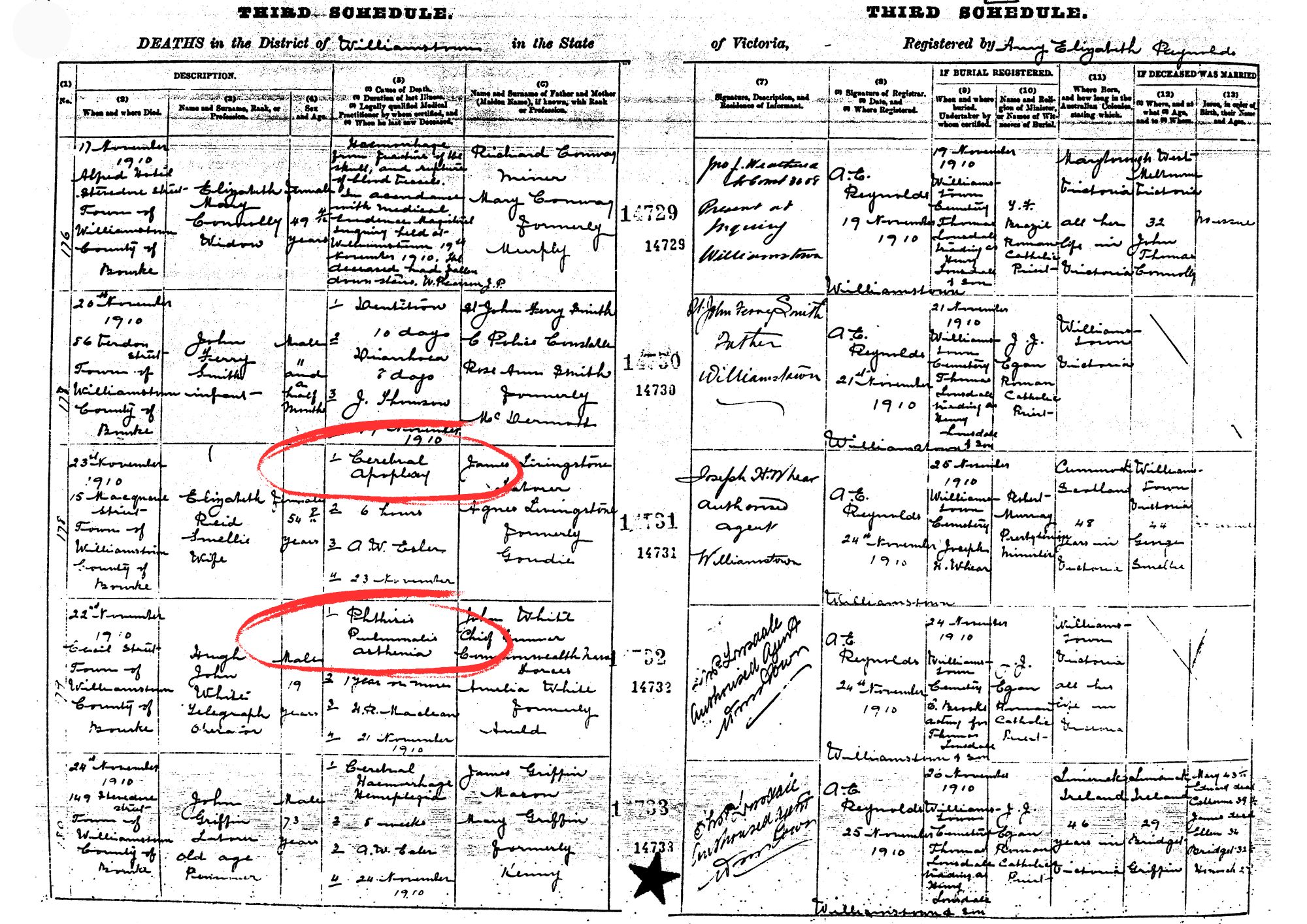

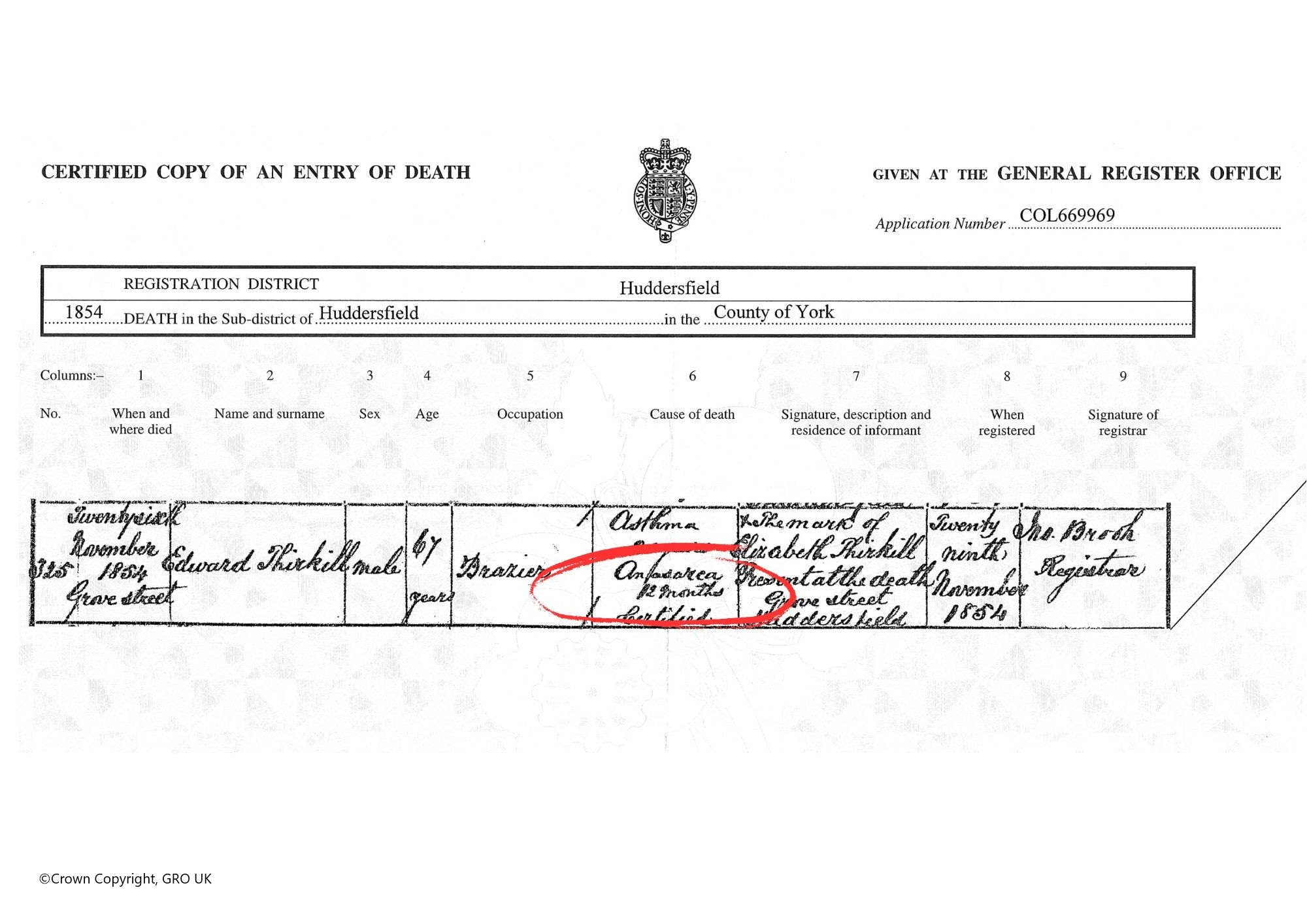

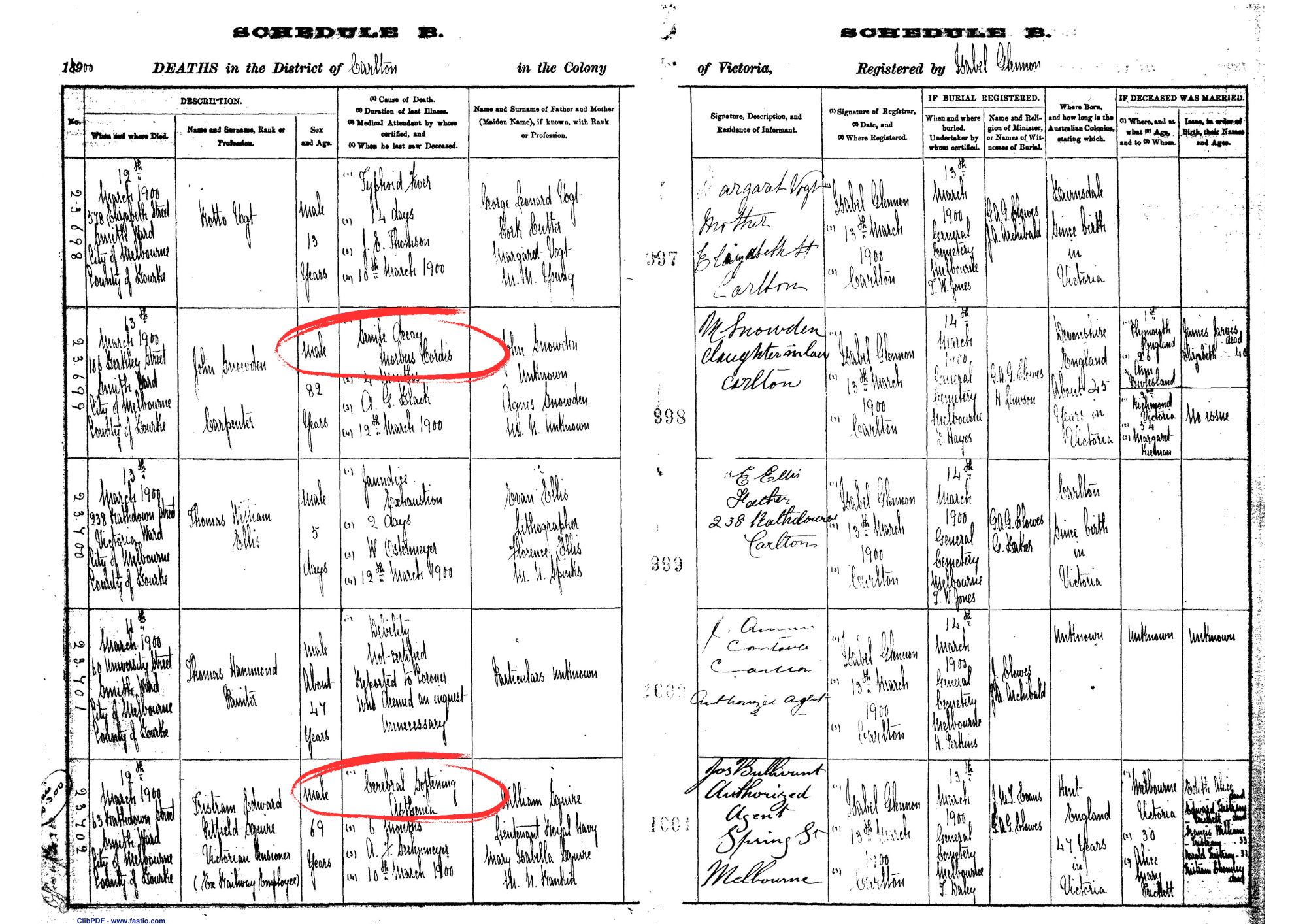

Medical language has evolved alongside medical understanding. A nineteenth-century doctor could describe “phthisis” where we would say tuberculosis, or record “apoplexy” for what we now recognise as a stroke. Others wrote “dropsy” to describe the swelling of the body caused by heart, liver, or kidney disease.

The Dictionary of Practical Medicine (James Copland, 1858) defined “dropsy” as “a morbid accumulation of serous fluid in the areolar tissue or cavities of the body, often symptomatic of disease of the heart or kidneys.” Such definitions reveal how doctors described what they observed, even if they did not fully understand what lay beneath.

Sometimes the terminology was more poetic than medical. A death attributed to “decline” could mean malnutrition, tuberculosis, or simply old age. “Senile decay” or “senile heart” reflected the gradual weakening of the body and its systems. “Asthenia” — meaning loss of strength — and “marasmus” — the body’s wasting through lack of nutrition — both captured the slow fading of vitality without naming a specific disease.

Reading between the lines

For genealogists, old causes of death can be intriguing, but they also require careful handling. They invite us to interpret rather than assume.

A cause like “apoplexy,” for example, may suggest a sudden collapse — but the exact mechanism could have been cerebral, cardiac, or vascular. “Anasarca,” describing severe generalised swelling, could point to heart failure, kidney disease, or even long-term malnutrition. The term itself doesn’t give us an answer; it gives us a clue.

Context is everything. Age, occupation, locality, and historical events can help us interpret these entries with greater insight. A death from “pneumonia” in a frail elder means something quite different from the same diagnosis during an influenza epidemic. “Childbed fever,” common in nineteenth-century records, tells a story not just of infection but of the medical practices and social norms surrounding childbirth.

When we interpret old medical terms, we are translating not only language but worldview. To read “marasmus” or “senile decay” is to step into a time when disease and decline were understood through visible signs, not pathology. It calls for both curiosity and empathy: curiosity about what the term meant in its medical context, and empathy for the human story it represents.

These old words remind us that death certificates record more than loss. They reflect the limits of medical knowledge, the evolution of language, and the human need to make sense of the end of life. Behind every unfamiliar phrase is a person, a family, and a moment in history.

What we find in those fading lines is not just how someone died — but how a community understood living, dying, and caring for one another.